Learning about yourself

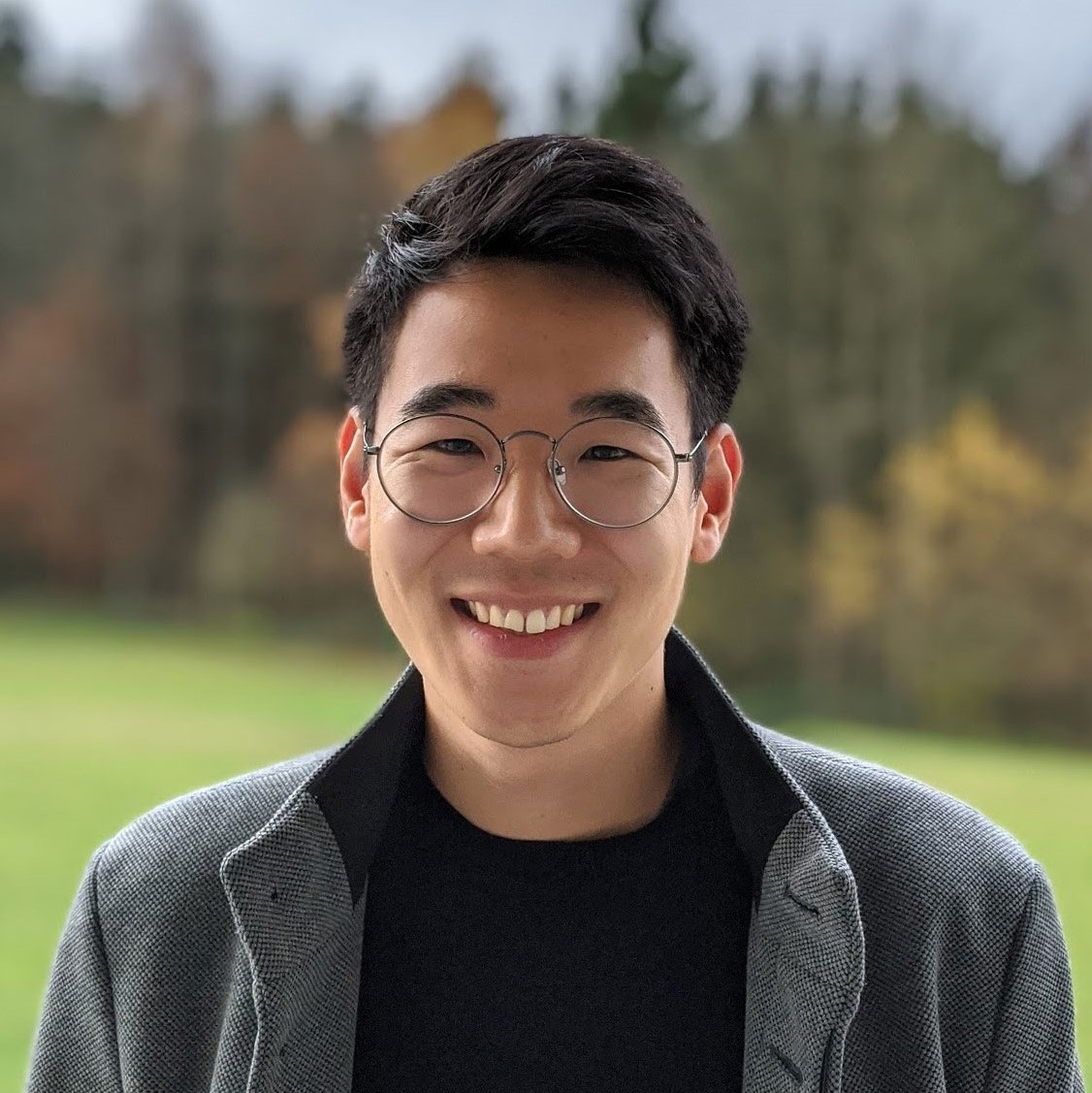

David Dao recently defended his doctoral thesis, conducted in the ETH Systems Group under the supervision of Professors Ce Zhang and Gustavo Alonso. His childhood fascination for Albert Einstein led him all the way from Munich to ETH Zurich. During his doctorate, he discovered a lot about himself, what he is passionate about and the value of thinking outside the box.

What does the beginning of an academic career in computer science look like?

In a series of three interviews, a doctoral student, a freshly graduated Doctor of Sciences and a young postdoc from the department share their motivations and experience.

– This article is part of the "Young researchers in computer science series" –

1/3 Xenia Hofmeier – Learning the hard way

2/3 David Dao – Learning about yourself

3/3 Chengyu Zhang – Following your heart

You studied in Germany, intending to come to ETH Zurich for your doctorate. Did you know early on that you wanted to do research?

I already knew when I was five. Or at least I knew that I wanted to be a scientist. I was always reading books about how the world works and I was fascinated by physics and science. Growing up in Germany, I soon came across Albert Einstein. His ability to think outside the box fascinated me and inspired me to visit the places he had visited: Munich, where he studied, and ETH Zurich, where he graduated in physics and met his first love.

I chose to become a scientist very early on, so I researched what it takes to become a professor, which studies I needed to do and so on. By the time I started my doctorate, I think I was very prepared; I knew how important it was to choose the right advisor and make the best of my time at ETH.

Is it difficult to get a position as a doctoral student at ETH Zurich?

Yes, it is very competitive. I did my Bachelor’s and Master’s at good universities in Germany, but that is not enough to get accepted for a doctorate in computer science at ETH Zurich. I understood that I needed to have publications, as well as other good schools on my CV. I therefore did my Master’s thesis at MIT in Boston, during which I managed to publish several articles. I also took a year off before my doctorate and worked for a company making self-driving cars in Silicon Valley. I needed this time to find a topic that I felt passionate about, but it likely also helped my application to ETH. During my Bachelor’s and Master’s, I took every chance I got to visit Zurich and I came to student information events to make sure I was prepared.

How did you meet your supervisor?

I contacted him shortly before he started his group. His appointment had just been announced and his research field fit exactly with what I was interested in: applied but still theoretical enough. The first time we talked, we knew right away this would be a good match. I was one of his first students and felt very lucky to be able to help him establish his group here.

What has been your experience as a doctoral student in such a young research group?

I loved it. I was fortunate that my advisor gave me great freedom to do what I wanted to do. Being there at the very beginning of the group was an opportunity to help shape some initial and highly significant work that is now fundamental for us and in the field of machine learning.

Since he had just become a professor, it was an open playground where we could ask any question we wanted. We focused on how much a data point is worth: “If you would pay someone for a data point, how would you decide its value?” This apparently simple question evolved into my whole doctorate. Within the first two and a half years, I published most of the important contributions that make up my thesis. This gave me the freedom to then go on and explore other avenues and look at slightly riskier projects.

In addition to my research, I also took on many other responsibilities, such as managing our internal communication and project management channels, the evaluation of potential students and, of course, teaching – which I loved. The first two years were intense, but I had a great time working closely with Professor Zhang to set everything up.

What does it take to do a doctorate?

I would never recommend that anyone do it for the title alone; you need to know what you are signing up for. I believe there are two types of doctoral students. On one hand, there are people who need a plan, who need instructions on what to do and who need close supervision. On the other hand, there are people who need more autonomy and the freedom to set their own course. They require different types of advisors.

I am someone who doesn’t need a lot of supervision. I have been researching what it means to be a scientist almost my whole life and I came into the doctorate very prepared. I also like to explore open or risky ideas and I needed a supervisor who could trust me and allow me to be creative.

I think that if you want to start a doctorate, you need to understand the kind of person you are. If you need more planning and supervision, having someone who gives you too much freedom is detrimental to your career, but the opposite is also true.

“If you want to start a doctorate, you need to understand the kind of person you are.”Dr David Dao, former doctoral student in the ETH Systems Group

How did you choose your projects?

A lot came out of this initial question of “How much is a data point worth?”. After that I also worked on several projects that were not strictly part of my doctorate, having more to do with environmental AI. I started in this direction when, after finishing an initial set of papers, I wanted to explore how we could apply this question to real-world problems: If you know how much the data is worth, how do you pay people, for example? This led me to look at environmental data sets, like pictures of trees taken by local farmers to protect a forest. I also believe that climate change is the single most important challenge humanity is facing right now, and I wanted to focus on that.

How do you manage the expectations or requirements of the doctorate with your need to think and work more outside the box?

For me, the doctorate is a precious period in life where you are given the trust and the freedom to focus on something you deeply care about. It is a time to understand who you are, find yourself and realise what is important to you. I am very proud of my thesis, for instance, but I cannot imagine myself as a professor working on this topic for the rest of my life. I would be happier doing interdisciplinary research with many collaborators or going into the field and seeing the impact of my work on local marginalised communities.

Our education should not prepare us to become professors, but rather to go out in the world and do something meaningful with our lives.

In hindsight, I am very thankful to my advisor for being so open about my ideas and allowing me to follow these crazy research directions. It took my initial research into unexpected fields and areas. But I know that he is an exception. Not many professors would allow that, although letting your students take risks and sometimes step outside of the traditional path is also very valuable for research. You get a lot back by leaving your comfort zone; you become more confident of your own abilities, including raising money and leading research projects.

In the end, it is probably a trade-off: listen to your advisor and fulfil the academic requirements, but be ready and brave enough to step outside the box. You will need to be able to work independently when you don’t have a supervisor anymore to give you advice.

You communicate about your projects more than most students. Is this particularly important?

It is. How can you inspire the next generation otherwise? I was never a natural-born speaker, but with time I realised that if you care about your work as I do, you have to talk about it. I care deeply about our environment, and I want to show alternatives to careers at big tech companies, and show that people working in AI and computer science can make a difference in areas where urgent action is needed.

If you’re not the one championing your work, no one is going to champion it for you. And if you don’t speak up about issues that matter to you, other people are going to speak up, and they might not say the right things.

What is the process of writing papers as a doctoral student?

Writing papers is hard, but it gets easier. Many students struggle at the beginning, especially if English is not their first language, but then you learn a sort of hidden language: not really English, but “academic” English. After some time, you also learn that it is not only about the language but about what is important to emphasise, how to write it clearly, how to make nice figures and how to make sure the experiments are what other researchers want to see.

You learn how to defend your work against counterarguments and identify where potential problems could be.

But that’s not the whole story: a paper that is not cited soon after publication will probably never be. If you want your work to be impactful, you need to go further, talk about it, open source your code and make presentations that distil years of work into easily understandable material. It is difficult and you need to be observant because no one teaches you this.

Was writing your thesis different?

I enjoyed writing my thesis. I had to cancel side projects and social commitments for a couple of months, but I am proud of the result. I took time to reflect on work that, in some cases, I did years earlier, to think about the motivations behind it and its implications over time.

The challenge is to make it enjoyable for the reader. It should not be an accumulation of all your papers. It should tell a story, with a narrative taking the reader through the steps of your research over the years. I feel that if you have been following your heart and enjoyed your thesis, you will find this common thread that has always been guiding it. Of course, I also snuck in some quotes from Einstein.

What is next for you?

I will take some time off to dedicate to GainForest, a non-profit organisation I created during my doctorate. GainForest currently supports 27 organisations in the world with tree planting, using technology to pay people who have the highest stakes in reforestation and helping with data collection. I want to stay in academia and become a professor in the long run, but for now, I will take this time to see how far I can develop GainForest.

I think it makes me a better scientist if I go out into the world, do something different and then come back with a fresh mindset, knowing what problems I should tackle. Science is something creative, almost like making music: you need to stay inspired and creative rather than settling in one place and letting everything become too mechanical and routinised.

“I think it makes me a better scientist if I go out into the world, do something different and then come back with a fresh mindset, knowing what problems I should tackle.”Dr David Dao, former doctoral student in the ETH Systems Group

Have you already given any thought to applying for postdoc or faculty positions?

I have. I have many friends on this path who shared their journeys with me, and I am aware of the sacrifices and struggles of starting as a young professor, like the difficulty of choosing where you will be appointed. I wish academia would be more friendly regarding work, life and family, but it is mostly up to supply and demand.

I already have an offer for a postdoc, and I am also looking into different funding options, but these are still open and I will only decide when I feel ready. I would not just take any position: the more I know about myself, the more I realise how important it is to never sacrifice your family and friends under any circumstances. Otherwise, one day, you will regret it.