Starting a company is like paragliding

For a two-part interview, we visit our alumnus Tobias Nägeli. In this first part, we learn more about the turbulent times of founding the spin-off Tinamu and how Tobias and his three co-founders managed to find the right market for their technology. We also discover the connection between starting a business and his two hobbies, marathon running and paragliding, and how a tragic accident influenced his willingness to take risks.

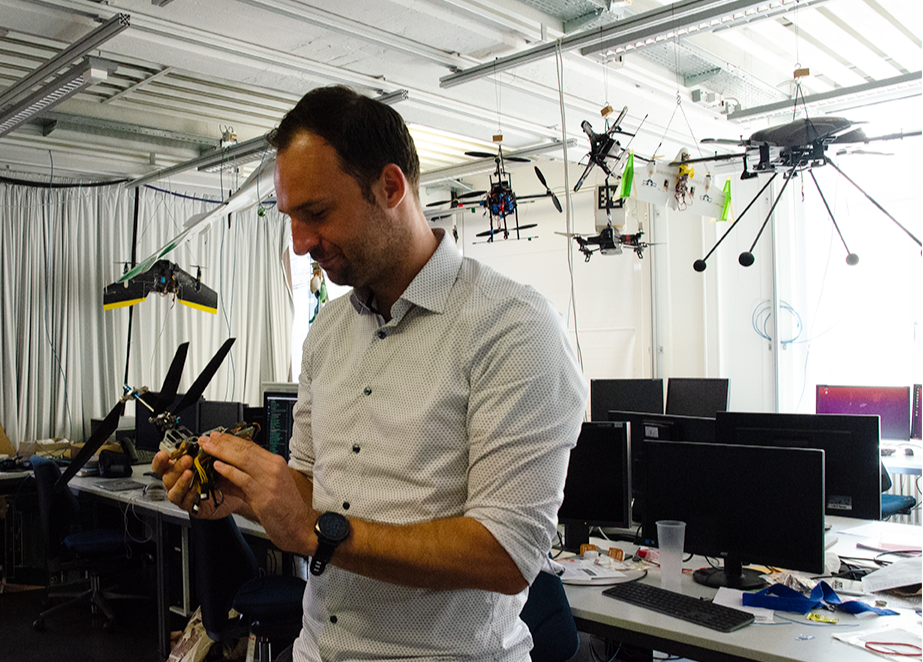

Tobias Nägeli studied electrical engineering and information technology at ETH Zurich from 2006 to 2013. He switched to computer science for his doctorate, which he completed in 2018 under the supervision of Professor Otmar Hilliges. During his studies, Tobias focused on drones. His dissertation, which dealt with the automation of drone flights, led to the founding of the ETH spin-off Tinamu in early 2019.

“Do you see the green area? That's where the paragliders take off.” Tobias Nägeli stands on the observation deck of the Üetliberg and points to a meadow a few hills away. However, on this sunny late summer day, no paragliders are around. Today, both literally and metaphorically, Tobias has chosen to stay grounded, although he enjoys flying professionally and personally. The paraglider is the CEO of the spin-off Tinamu. The company conducts industrial inspections with autonomous drone flights. They specialise in bulk goods.

But that was not always the case.

ETH spin-offs derive their business ideas from research. What did you work on during your dissertation?

At the beginning of my doctoral studies, I wanted to explore drone navigation without GPS. The drone would rely solely on camera images for orientation. However, I soon discovered that others had already delved into this topic extensively. Publishing something that had already been thoroughly covered proved to be challenging. To publish a study, one must either be exceptionally skilled or work on something completely new. Eventually, I stumbled upon something: the drone determines its position based on fixed points that appear in its camera image. I was able to reverse this process. You specify the desired positioning of the fixed points in the image, and the drone then searches for the corresponding position. This realisation would not have been possible without the freedom to experiment provided by my professor, Otmar Hilliges.

We originally wanted to use this discovery to automate film and sports shots. There are two challenges in cinematography. Traditionally, drone control requires two people – a pilot and a camera operator. The two must be extremely well-coordinated. Additionally, camera movements are repeated on film sets, often using a camera dolly. This involves attaching a camera to a cart that moves on rails. Using drones would allow for more flexible camera movements, but precise flight repetition was almost impossible. For this purpose, drone flights would need to be automated. While GPS data enables automated flights, it is limited to outdoor environments. Therefore, the drone should navigate independently of GPS and know its own position. The technology I developed makes this possible. As a result, our product initially attracted attention in the film and sports industries.

Why did you change direction, then?

Several television stations invited us to showcase our technology. They even expressed interest in purchasing the product once it was market-ready. However, we realised that our product was not yet mature enough. Nonetheless, we strongly believed in our idea, and the potential demand led us to establish a spin-off. Then, new challenges emerged: for sports and film recordings, we would have had to continuously conclude new contracts. Furthermore, our employees would have had to transport the equipment and set it up from scratch on-site. This was not practical for us.

So, you changed direction and focused on industrial applications. How did that happen?

While externally focusing on films and sports, we also internally thought about the industrial application of our product from the beginning. We have two scenarios where the technology can be deployed in industry. One is periodic inspections, which are carried out approximately every one to two years. The other is continuous monitoring of premises and their contents.

Axpo approached us early on with a project. They wanted to use our technology for autonomous flights in large facilities, which in their case were dams. Whether we fly on a film set without GPS or inspect dams, the technology remains the same. Instead of installing cameras everywhere or having to use people, a drone can inspect or continuously monitor a location. Multiple individuals can review drone images, enabling the early detection of hazards. Then, there are soft factors such as ensuring the safety of employees, as there is no longer any need for humans to climb into the dam. Drones, therefore, provide real added value and help companies reduce their costs.

“Our technology has numerous applications, but we are interested in the challenge of dealing with large amounts of materials, such as bulk goods.”Tobias Nägeli

What helped you to attract more customers from industry?

What actually propelled us forward was the pandemic. Before the pandemic, we would invite people to our office and set up a test track, but people only began to be impressed during the lockdown, once we integrated a demo into our online presentations. The demo allowed interested parties worldwide to explore our office autonomously with drones through a website. They could log in and see a live stream where we would wave to them from our workstations. As a result, we not only found new investors but also gained customers with diverse needs. Our technology has numerous applications, such as the automatic inspection of freight trains to ensure proper loading or the monitoring of greenhouses to assess plant growth. We then decided to focus on commodity trading.

Why is commodity trading so attractive to you?

We are interested in the challenge of dealing with large amounts of materials, such as bulk goods. It is difficult to determine the amount of material in a pile accurately. Although you can measure the weight of what goes into a warehouse and what is taken out, it is prone to errors. In fact, companies are already offering a service to solve this problem. However, these solutions require physically sending people into industrial warehouses to check the inventory. This process takes about two weeks for the data to be made available. It is expensive and time-consuming, so these inspections are usually carried out monthly or even quarterly. Most companies, however, desire more continuous inspection, and this is where our system comes in. Our drones don’t need to be fully autonomous because people are always working in the warehouses. Someone can place the drone inside; similar to a vacuum robot, it then does its job.

How did you win your first customer in this field?

Daniel Meier, one of my co-founders, and I went to Antwerp to land our first contract. However, we were overwhelmed by the size of the warehouse. While our technology was advanced then, it still needed to be developed further. Therefore, we wanted to test and refine it at a location in Switzerland before making it available to the company. So, we simply went on Google Maps and searched for suitable places. That's how we came across Kibag in Regensdorf, which had a similar warehouse and was located near us. We asked if we could use their facilities to test our drones. The technical manager, Urs Fischer, agreed immediately, and we installed our system. After a few weeks, Fischer wanted to see our data. When we shared it with him, he was impressed by its accuracy and quality, and he wanted to use our services going forward. So, we accidentally gained our first customer in Switzerland.

What lessons did you learn from this initial phase and subsequent reorientation?

An important realisation was that technology alone does not guarantee the success of a product. Just because something is technically impressive doesn't mean it will ensure the success of a startup. Identifying market problems, testing the market and discovering the scaling potential for the product to thrive are essential. This often requires the support of individuals with design skills or entrepreneurial expertise. Sometimes, founders hold onto their ideas even when there is no market for them. That's why it is crucial to be open to feedback and face reality. Just like when we had to accept that the film and sports industry was the wrong market for us.

As we descend from the observation platform, Tobias points again towards the distance, in the direction of Valais. He tells me about an experience he had when flying with his paraglider from Fiesch, intending to land in Kandersteg. However, when Tobias reached his destination, he couldn't spot the train station from above. He still decided to land and saw the signpost for Adelboden after his descent. “It wasn't a big deal. It simply taught me that I probably need to practise map reading a bit more,” he says with a smile. Reflecting on his career path, Tobias mentions that nothing has ever gone terribly wrong and that he takes things as they come. “As an engineer, I'm realistic and assume that projects usually take longer than planned and unexpected obstacles can arise. For example, something unexpected always comes up when negotiating a new contract. It's like marathon running, another one of my hobbies: you can prepare really well, but just before the next race it’s guaranteed that you will twist your ankle or have a bad night's sleep,” Tobias explains. That's why he tries to keep his expectations low and then be positively surprised. Nevertheless, he sees a possible way out in every situation and a solution to every challenge. “I'm basically an optimistic, pessimistic realist,” Tobias laughs. This carefree and trusting attitude benefits him at work and in paragliding.

Have your carefree nature and optimism ever helped you in a difficult situation?

Yes, during my doctoral studies, I decided to go paragliding in Austria before an important conference. I felt overly confident, which turned into a significant, albeit painful, lesson. I crashed the paraglider but luckily managed to twist my body just in time to land feet first on the ground. Nonetheless, I suffered several fractures in my legs, ribs and back, but I did not require surgery. At first, I didn't even realise the severity of my injuries and even walked towards the ambulance. I spent a week in an Austrian hospital before being transferred to Switzerland. Initially, I couldn't walk at all, but with the help of splints and crutches, I gradually started limping again. I remember thinking, “If it stays like this for the rest of my life, it's okay as long as I'm alive.”

Rocks surrounded the crash site, so a fall even a few metres to the right or left could have ended badly. The head doctor assured me that I would eventually be able to walk normally again, but running would no longer be possible. That was hard to hear since marathon running is one of my hobbies. After my discharge, I was on sick leave for three months. But after just one day, I got bored. What does one do at home on a Monday morning? I didn't have Netflix back then, and although I enjoy watching trash TV, spending the whole day in front of the television was not an option for me. So, on Tuesday morning, I limped to ETH and announced to my professor, Otmar Hilliges, “I'm back at work now.” He was initially uncertain how to reconcile it with my sick leave, but we found a solution together. Three months later, I completed a half marathon, and after eight months, I ran an ultramarathon. When someone claims something is impossible, I am determined to prove them wrong. However, I have become more cautious when it comes to paragliding. I have learned that pushing yourself to the limits is not always wisest. Sometimes, it's perfectly fine to take a step back and say, “That's enough for me.”

“Both paragliders and founders must be prepared to take risks and venture into the unknown, but always within a framework that ensures sufficient safety.”Tobias Nägeli

As Tobias shares more stories about his paragliding adventures, he spontaneously notices several parallels between the hobby and the founding of his spin-off. When paragliding, it is crucial to trust your instincts. Flight decisions often must be made in split seconds, leaving little time for extensive analysis. A mistake could have catastrophic consequences. When flying over large distances, you must simultaneously keep an eye on the wind, the terrain and other flyers. Additionally, it is important to remember that eventually you need a safe landing. However, if you always fly in a way that ensures a landing, you will simply remain in the same place. Paragliders must be willing to take risks and venture into the unknown, but always within a framework that ensures sufficient safety and survival. Finding this balance is equally challenging for Tobias in starting a company. However, he has learned to rely on his instincts as a reliable guide. Another aspect is patience. Sometimes, Tobias experiences neither ascent nor descent while flying. In such moments, he must stay in place and patiently wait for better conditions. If you fly hectically back and forth, you end up on the ground. The same applies to unexpected events in the business realm, such as geopolitical conflicts or a pandemic. In such situations, it is vital not to act impulsively. Instead, you should hold on to your conviction and wait for the right moment, explains Tobias.

Read the second part of the interview: "At heart, I remain an engineer"

In the second part, we visit Tobias at his company, and take a journey back to his time as a student at ETH Zurich. Tobias gives us an insight into his former student days and tells us how he met his three co-founders. Additionally, we learn more about the skills from his studies that benefit him today as CEO.