"We didn't want to be seen as contrarians who were just causing a commotion"

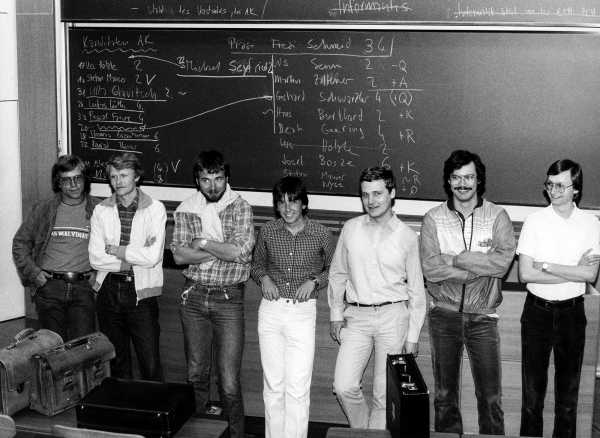

Fredi Schmid was a co-founder and the first President of the Association of Computer Science Students at ETH Zurich (VIS). In the interview he remembers the founding, the parties, and studying computer science in the 1980s.

This interview was originally published in Visionen, the magazine of the Association of Computer Science Students (VIS).

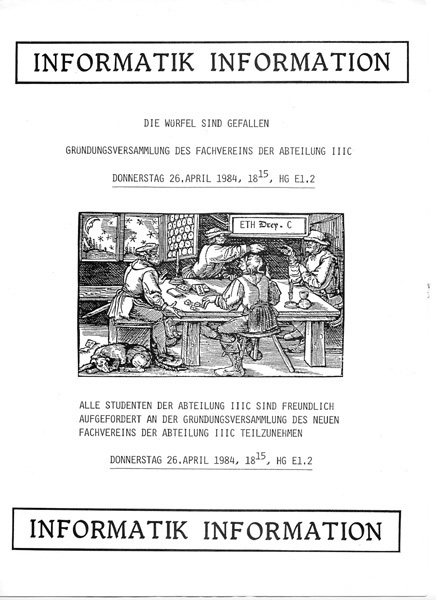

Fredi Schmid, what inspired you and your fellow students to found VIS in 1984?

We noticed that other departments had their own student associations. That's when we got the idea of founding one for computer science as well. Without knowing exactly what such an organisation does and what it brings to the table, we created the VIS. Fortunately, we had someone with us who had studied law before computer science and was able to help us draw up the statutes.

How did the division IIIC, the precursor to today’s D-INFK, react to the VIS?

It was a great working relationship. Professor Zehnder in particular, who has also done a lot for computer science on the socio-political level, approved of the fact that we finally had an association to represent the students, and explicitly supported us. From then on, the VIS board was often invited to sit on various department committees. Although we were mostly there to listen, it was quite interesting to follow grade conferences or discussions about the curriculum, which was still being developed back then.

What were your goals in those first years?

We wanted to publish a magazine – one which was better than the other student associations. We were fortunate that computer science was very new and in high demand in the industry. This made it easy to get companies to place advertisements. We soon had enough money to print 2000 copies of "Visionen". Of these, 500 went to the industry. Through this, we quickly had an internal and external means of communication. Other than that, we created the famous VISKAS party – "Very Important Session at Katzensee" – and made past exams and solutions available to students.

Did the students appreciate your efforts?

Yes, the VIS' activities and measures were well received. The past exam papers were particularly popular and "Visionen" started many a discussion. I held an introductory VIS event for first-semester students, and I got recognised many years later by people who had attended it. Our work got noticed and was appreciated.

What did the VIS office anno 1984 look like?

The department provided us with an attic room at Clausiusstrasse, the home of computer science at that time. We were equipped with an IBM ball-head typewriter, a luxury model with a correction key and a 100 character memory. We had also received an Olivetti computer as a gift from Olivetti. If I remember correctly, there was no such thing as free coffee for students at that time.

How did you organise yourselves in the time before e-mails and Slack?

We had weekly meetings and sometimes ran into each other in lectures. And we talked on the phone – via landline, obviously.

What were the VIS parties like in the 80s?

The first VISKAS was nice. We had a barbecue at the Katzensee with 150 people. It was fun to organise such a big event for our fellow students. Then there was the annual fondue dinner with a smaller group. Other than that, I don't remember many parties. Except maybe that one board party.

What happened at the board party?

One of the compulsory lectures we had at that time was really bad. So, I voiced some criticism over the quality of the core lectures in "Visionen". This caused quite an uproar and I was summoned by several professors to explain myself. The magazine also went out to people in the industry and some felt that my article was casting the department in a negative light. Shortly after that, the board party took place. It went on for quite some time and we really got into the spirit: something must be done – now! As a result, we wrote a rather harsh article about this specific lecture for the next "Visionen". People continued to mention it to me 20 years later. However, we didn't want to be seen as contrarians who were just causing a commotion. Therefore, we initiated lecture evaluations and they produced a very clear picture of this lecture. The professor did not remain at ETH for much longer after that, although that certainly wasn’t just down to us.

What other experiences from your time spearheading VIS have stuck with you?

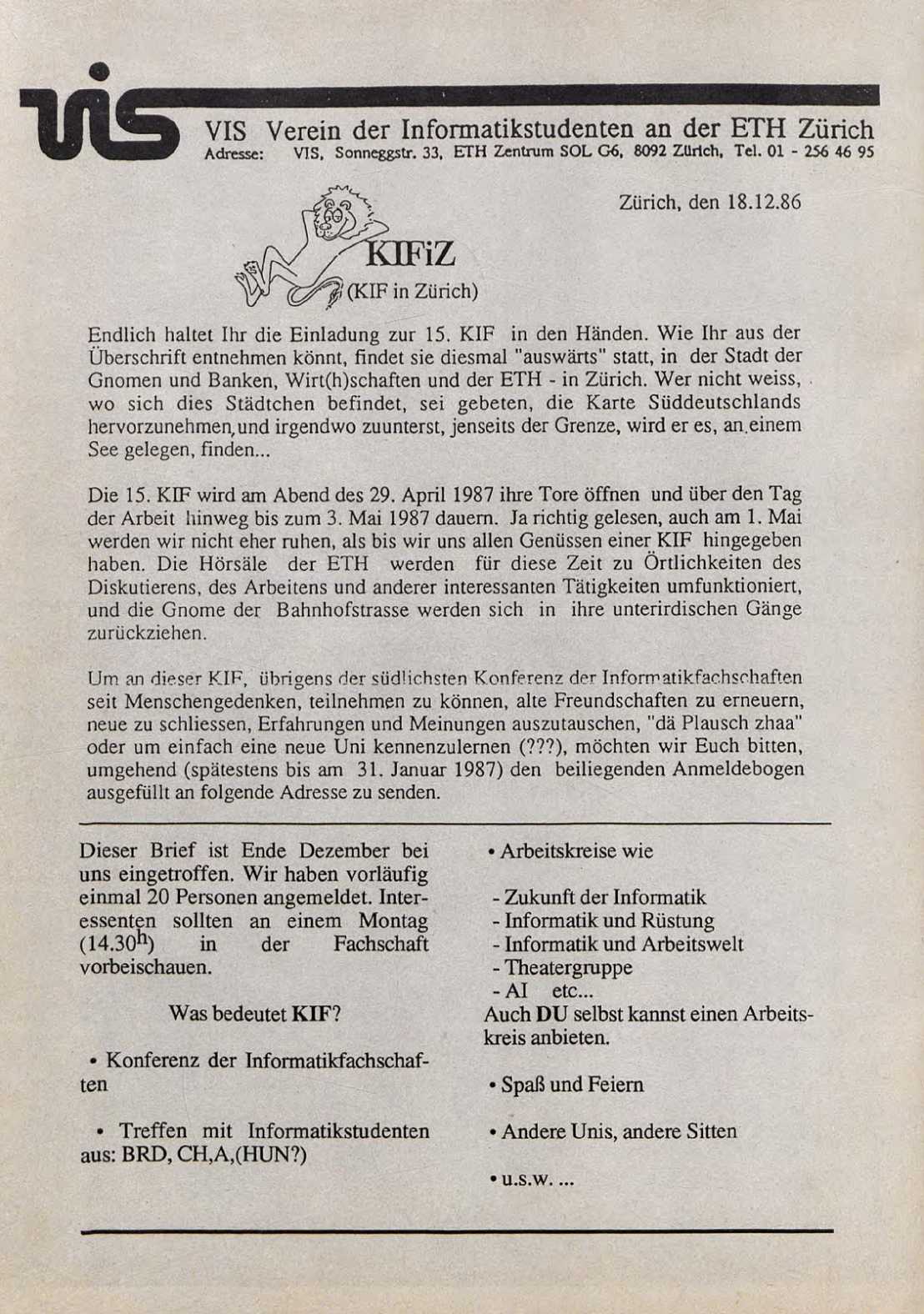

In 1987, we organised the Konferenz der Informatikfachschaften (Conference of Computer Science Students, KIF) in Zurich. This is a biannual gathering of computer science students from German-speaking countries. Computer science was in such high demand with the industry that I called a general manager of Credit Suisse and immediately got the money for the KIF. We were able to house, feed and entertain about 700 students for a week. We flew people in for panel discussions and organised a tram city tour for 700 people. It was fun to operate on this large scale for a change.

Did your studies take longer because of your VIS engagements?

No, it all happened during the normal study period. I did take a gap year, when I extended my industry internship to eight months and used the remainder of the time and the money I had earned to travel. But that had nothing to do with the VIS.

What did your involvement with VIS bring to your later life and career?

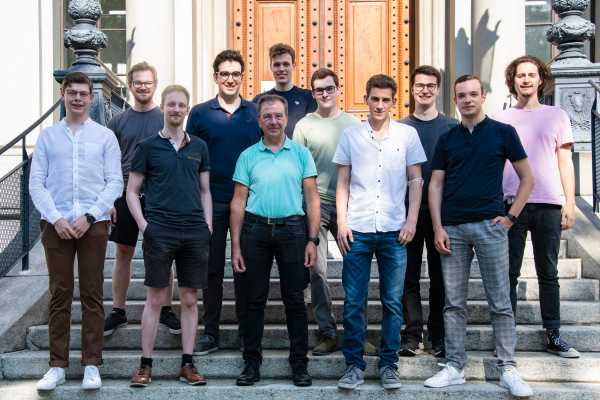

Organising something and getting things done was a very valuable experience. I’m not active on the board of any associations today, but of course I have gained a lot from the VIS. I’m pleased that we were able to start many activities back then which are still going on today.

And how did you benefit from studying computer science at ETH Zurich?

At the beginning of my career, my work was very technical. In my first job, I wrote a translator from Modula-2 to C – actually a compiler that "misused" C as a high-level assembler. It was a privilege to learn from luminaries like Niklaus Wirth, the inventor of Modula-2. However, since I have always been more of a generalist, I also appreciated the so-called environmental subjects. These were untested compulsory subjects outside of computer science: economics, law, sociology, industrial psychology, etc. I also benefited from this in my professional life as I later made a deliberate switch to coordinative and management functions and, for example, took care of part of the IT outsourcing at Swiss Re. Today, I work in purchasing and have hardly anything to do with the technical aspects.

"Moore's Law was already known at the time. But the idea of 4.2 gigabytes of memory seemed absurd when you were used to 64 kilobytes."Fredi Schmid

You began your studies in 1982, when the computer science curriculum was brand new. What motivated you to choose this subject?

I liked mathematics at school. Learning different number systems was an exciting experience for me. However, I felt that mathematics alone was too dry to study. I didn't even know what a mathematician does after graduation. I wanted something practical. But the classic electrical engineering programme seemed overloaded to me. A friend of mine had just started the new computer science programme at ETH. I visited him in Zurich for a day and knew afterwards that this was the thing for me too.

Which computer did you learn to code on?

We had an excellent mathematics teacher at the cantonal school in Solothurn, who also knew a lot about computers. He had a small computer with a display made of superimposed filaments. Inputs were made in the octal system: four levers had to be flipped for each letter. You thought twice about adding comments to such programs! At ETH Zurich, we learned Pascal on Apple II computers. They had a screen of 24 by 80 characters, with green glowing letters, and 64 kilobytes of main memory. So, you couldn't program an array from 1 to 100,000.

Has the rapid development of computer science since your student days surprised you?

As far as the development of computing power is concerned, Moore's Law was already known at the time. But exponential growth is hard for most of us to grasp, as the pandemic has demonstrated. We knew in theory that 32 bits would eventually not be enough for addressing, but the idea of 4.2 gigabytes of memory seemed absurd when you were used to 64 kilobytes. The worldwide networking was something that, to my knowledge, no one anticipated. Who could have imagined in the 1980s that an Indian company would one day do IT for a Swiss company and that they could work together so easily thanks to the internet?

How do you think this development will continue?

I cannot possibly predict that. It is conceivable that breakthroughs in completely different technologies, for example in genetic engineering, will be combined in unforeseen ways with breakthroughs in computer science. New worlds will emerge that we cannot imagine today.

40 years D-INFK

In 1981, the computer science curriculum was introduced at ETH Zurich. At the same time, the IIIC division was established, which was the foundation for today's Department of Computer Science. On the occasion of its 40th anniversary, we present people and stories that have influenced the department over the past four decades.