“I wasn’t trying to save the world”

How does the Internet of Things change our lives? What does computer science mean for society? Before his retirement in 2020, Professor Friedemann Mattern studied small things in a big context.

Throughout his career, Friedemann Mattern was provocative. His research projects, from egg cartons that send a text message to warehouse management when they fall down to apps that reduce energy consumption, regularly attracted media attention. His lectures divided students’ opinions. He gave talks to federal councillors, advised CEOs and debated lawyers on the legal implications of self-driving cars. Was Mattern trying to save the world? “Not save it, but encourage it to think,” he says. “What do these new technologies mean for our society? For the economy?”

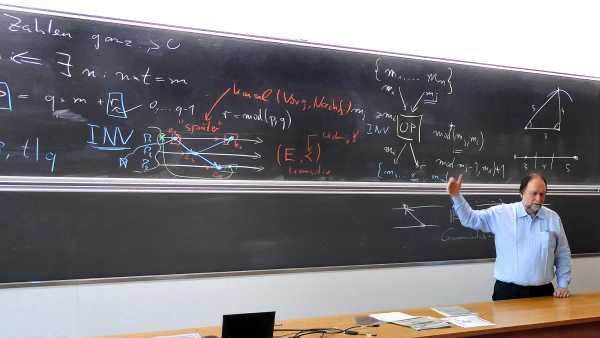

For 21 years, the now retired professor researched and taught at the Department of Computer Science at ETH Zurich in the field of ubiquitous computing, which makes everyday objects “smart”. “To German speakers, the term ‘ubiquitous computing’ sounds somewhat mystical and is difficult to pronounce,” notes the 65-year-old. Twenty years ago, he was the one who introduced the term “Internet of Things”, which was already familiar in the English-speaking world, into the German language.

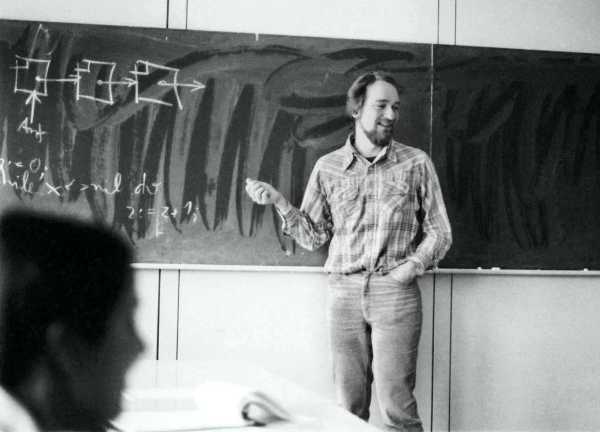

From an early age, Mattern learned to think critically. Born in 1955 in Freiburg, Germany, into the family of a diplomat, he travelled the world even as a child. His nine years of secondary school were spent at the International German School in Paris, where the enthusiastic teachers and the anti-authoritarian mood of the 1960s and 1970s sharpened his mind. Through family friends, he had his first contact with computers, and decided to study computer science at the University of Bonn – a decision he regretted almost immediately. “At the start, my studies were very theoretical and abstract,” he remembers.

“At the start, my studies were very theoretical and abstract, but I soon realised that a new world was opening up for me."Prof. em. Friedemann Mattern

Nevertheless, the young Mattern persevered and soon discovered a passion for his subject again by exploring far beyond the scope of the curriculum. “I realised that a new world was opening up for me,” he says. Still, the decision to stay in that world after graduation did not come easily to him. In a three-hour phone call, his advisor finally persuaded him to pursue a doctorate at the Technical University of Kaiserslautern.

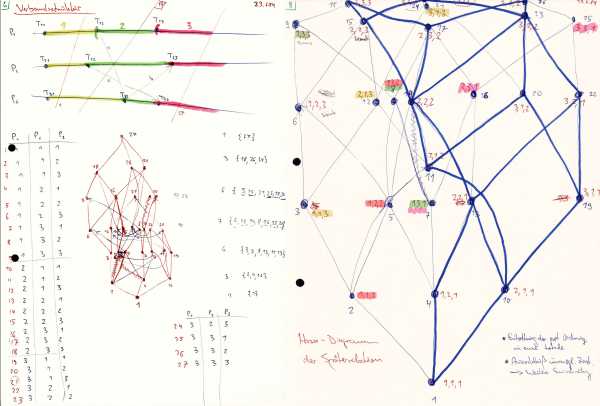

The soul of an engineer

His time in Kaiserslautern brought Mattern international recognition. Together with other researchers, he invented the vector clock: a software component that places time stamps on events that take place within distributed systems and thus captures the chronological order in which they occur. “To this day, that is my most cited paper,” Mattern smiles. “I have to admit, I am a little proud of it.” While still a doctoral student, he started giving a lecture on distributed algorithms, which was to remain popular with students throughout all stages of his career, right up to his retirement from ETH Zurich.

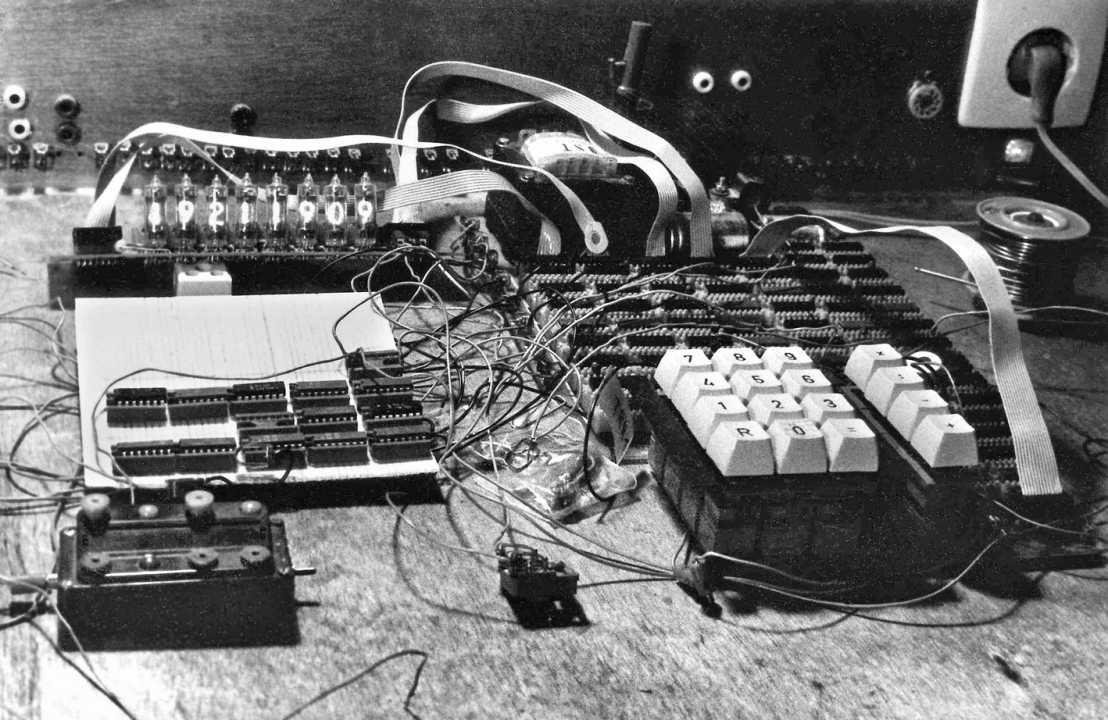

The young researcher’s future seemed certain. A professorship followed in Saarbrücken, then in Darmstadt. Mattern founded a graduate college and organised a seminar on his hobby, the history of computer science. Studying history sharpened his understanding of the present. “I realised that, if computers continue to get smaller, very soon it will be possible to do things that seem like science fiction today.” He wanted not only to observe what that would mean for society, but to help shape it. “I’ve always had the engineer’s soul in me, as well,” Mattern says. Even as a child, he had tinkered with electronics, built radios and calculators. That, too, drew him to the more physical aspects of computer science.

Just at the time of this change of heart, Mattern saw an advertisement for a professorship at ETH Zurich in the field of distributed computing. A new beginning, a blank slate. Should he risk it? “If you don’t try, you’ll regret it later,” warned Mattern’s life partner, also a professor of computer science. But even when he was offered the position, he agonised over whether to accept it. After all, in Darmstadt, he had a reputation, a network, popularity among the students… At ETH, uncertainty awaited him. “To this day, I am very grateful to ETH Zurich for giving me a lot of time to make up my mind,” he says.

Broadening horizons

In 1999, Friedemann Mattern began to set up a research group for ubiquitous computing at the Department of Computer Science at ETH Zurich. Owing to the advent of the smartphone, the new line of research surpassed his expectations. “The smartphone has three interfaces: to the person, to the internet, where all kinds of knowledge can be accessed, and – via sensors, Bluetooth and the camera – to the physical world,” Mattern explains. This makes it an ideal medium for the Internet of Things. When the first camera phones appeared around the turn of the millennium, the professor saw their potential: could software be developed, for example, to read barcodes on products with the still low-resolution cameras? Almost ten years later, Mattern’s doctoral students founded the spin-off Scandit based on this idea, which today employs around 250 people around the world.

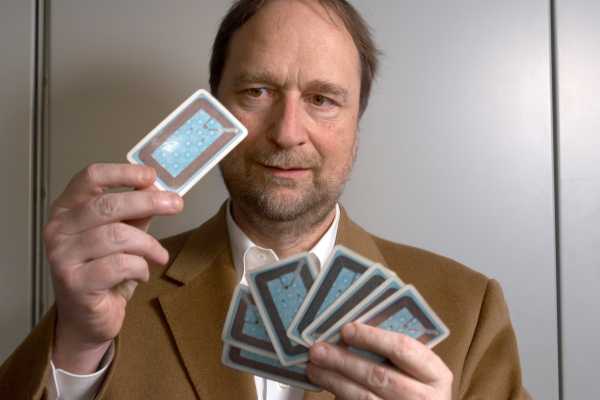

Numerous other research projects followed, some playful, some provocative: a gaming table with RFID playing cards to track gameplay on a mobile phone; dynamic liability insurance for a car that adjusts the policy in accordance with the policyholder’s driving style; a sensor for potted plants. The latter became another spin-off, Koubachi, which was acquired by Husqvarna Group in 2015.

The physical side of computer science: with the move to ETH Zurich, Mattern started to explore the Internet of Things, for example with this smart egg carton that notifies the warehouse management after a fall.

The physical side of computer science: with the move to ETH Zurich, Mattern started to explore the Internet of Things, for example with this smart egg carton that notifies the warehouse management after a fall.

Can you read barcodes with a mobile phone? Mattern and his doctoral students experimented with this technology using the very first camera phones.

Can you read barcodes with a mobile phone? Mattern and his doctoral students experimented with this technology using the very first camera phones. Several years later, this technology gave rise to the spin-off Scandit, which has 250 employees today.

Several years later, this technology gave rise to the spin-off Scandit, which has 250 employees today. Playful projects were also on the menu: Mattern demonstrates playing cards with an RFID chip. A special playing table transmitted the gameplay onto players' phones.

Playful projects were also on the menu: Mattern demonstrates playing cards with an RFID chip. A special playing table transmitted the gameplay onto players' phones.

Solving the problems of the 20th century with the technology of the 21st: the Smart Energy eMeter shows the electricity consumption on the smartphone and helps save energy.

Solving the problems of the 20th century with the technology of the 21st: the Smart Energy eMeter shows the electricity consumption on the smartphone and helps save energy. Valuable collaboration: Mattern worked with ETH professor Elgar Fleisch (right) and with industry on many of his projects.

Valuable collaboration: Mattern worked with ETH professor Elgar Fleisch (right) and with industry on many of his projects.

Mattern was never one to rest on his laurels. When the Internet of Things became a buzzword, he turned his attention to the next forward-looking field: smart energy. “We asked ourselves, can we use the smart technology of the 21st century to fix our 20th-century sins?” Whether reducing private energy consumption with the help of an app, helping power plant operators understand the latest technologies or giving a lecture on smart energy, once again he and his research group were at the forefront of the field. “Thanks to ETH Zurich’s excellent reputation, I always had good, adventurous doctoral students,” Mattern says. “Today, they are professors themselves, work at start-ups and in research departments of companies, and are helping to shape the future – that brings me the most joy.”

Mattern also brought his critical approach and his vast knowledge of the history of computer science into his lectures. What caused resentment among some students made him a favourite professor for many others. “I loved teaching,” he says. “Those students who were enthusiastic and asked questions made up for the negative feedback and the extra effort I put into preparing the lectures.”

During his time at ETH Zurich, Mattern broadened not only the horizons of students, but also those of the department itself. After acting as the patron of the Women's Support Network (now known as CSNOW) for a number of years, he took over as Department Head in 2010 and did everything he could to win the backing of his colleagues and the ETH Executive Board to cover emerging areas of computer science and to support promising young researchers. Thanks in part to his efforts, machine learning, human computer interaction and cybersecurity are now firmly established at D-INFK.

Supporting science

Despite all this, the researcher takes a sober view of the development of computer science. “The changes are extensive, but not unprecedented,” he says. “For example, the introduction of electricity over a hundred years ago was quite similar.” He is sceptical about the increasing media hype surrounding certain technologies. Artificial intelligence, for example, is neither as new nor as advanced as people believe, Mattern cautions. Too many false promises could damage the trust society places in computer science, he says. “Technology is not a given. Progress is possible, but it needs huge investments – and the industry will only invest if people are willing to spend their money on information technologies.”

Mattern also wanted to convey this nuanced view of his subject in his lecture Informatik II for future electrical engineers. As part of ETH Zurich’s Critical Thinking Initiative, he enriched the lecture slides with carefully researched historical material. He invested the first months after his retirement into the final version of this monumental manuscript. “I miss my lectures the most,” he sighs.

Although he is critical of the mandatory retirement of all professors at ETH Zurich at the age of 64 for women and 65 for men, Mattern is actively engaging with his new role as professor emeritus. “I have started to relinquish certain responsibilities,” he says. “But I still feel surprisingly little of it.” He remains active on various boards and committees inside and outside ETH Zurich, advising companies and universities. “I see that as my duty,” he says. “I want to continue to support science.” But he also looks forward to spending more time with his elderly mother in Freiburg, and also with his life partner, with whom he had been in a long-distance relationship for more than 20 years. “Sometimes I wonder what my life would have been like if I had gone into industry,” he admits. “Looking back, though, I think I made the right decision.”