ETH Zurich researchers participate in global study of city microbes

Researchers from the Biomedical Informatics Lab at ETH Zurich have participated in an international study to analyse the microbes in the air and on the surfaces of 60 cities, including Zurich. Their findings could help develop new drug therapies and learn more about evolution.

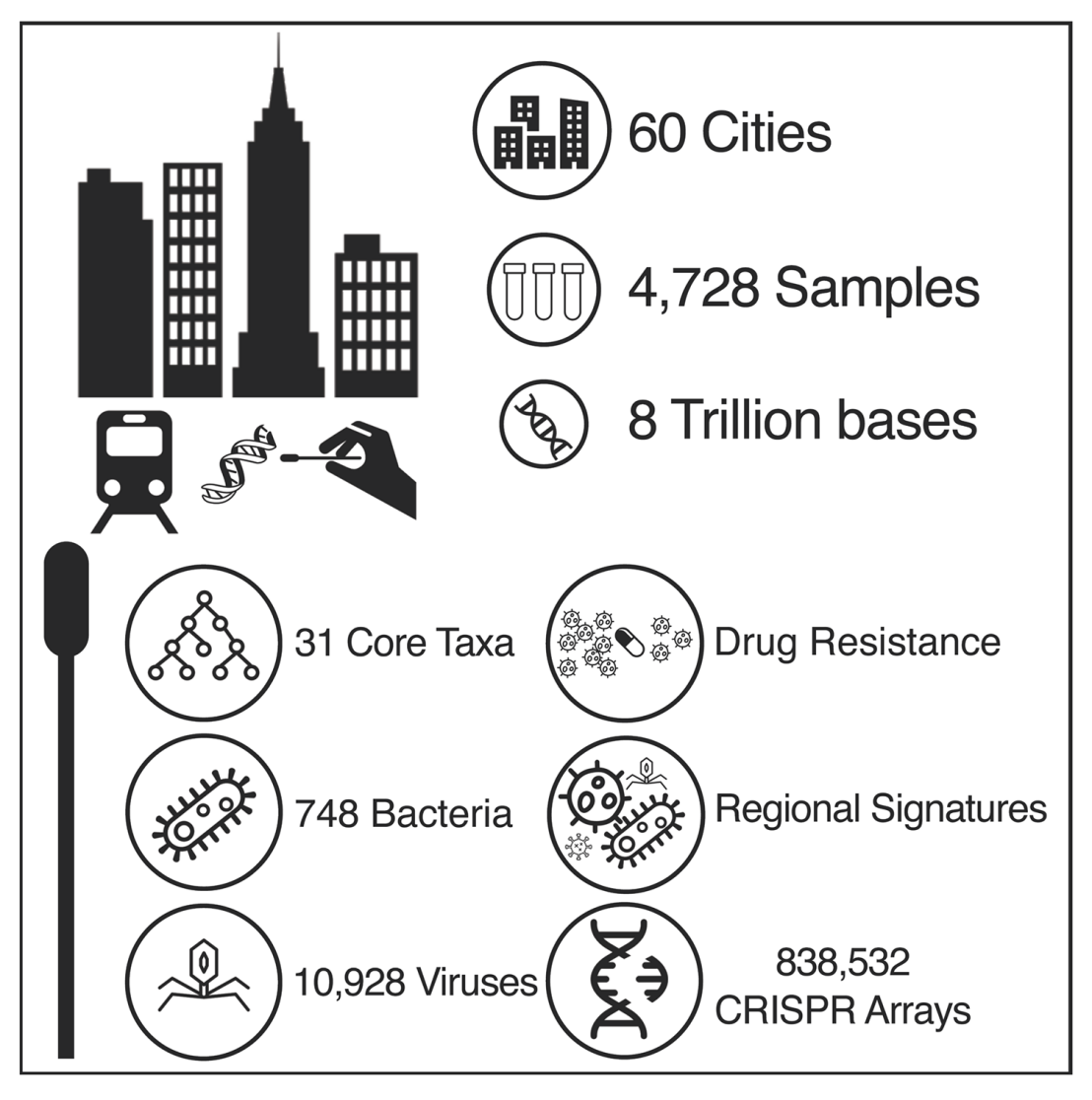

An international consortium has reported the largest-ever global metagenomic study of urban microbiomes, spanning both the air and the surfaces of multiple cities. The international project, which sequenced and analysed samples collected from public transit systems and hospitals in 60 cities around the world, including Zurich, Switzerland features a comprehensive analysis and annotation for all the microbial species identified—including thousands of viruses and bacteria and two archaea not found in reference databases. Researchers from the Biomedical Informatics Lab at ETH Zurich contributed to the study, which appears on May 26th in the journal Cell, with a companion paper published in the journal Microbiome.

“Every city has its own ‘molecular echo’ of the microbes that define it,” says senior author Christopher Mason, a professor at Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM) and the director of the WorldQuant Initiative for Quantitative Prediction. “If you gave me your shoe, I could tell you with about 90% accuracy the city in the world from which you came.”

The findings are based on 4,728 samples from cities on six continents taken over the course of three years, characterise regional antimicrobial resistance markers, and represent the first systematic worldwide catalogue of the urban microbial ecosystem. In addition to distinct microbial signatures in various cities, the analysis revealed a core set of 31 species that were found in 97% of samples across the sampled urban areas. The researchers identified 4,246 known species of urban microorganisms, but they also found that any subsequent sampling will still likely continue to find species that have never been seen before, which highlights the raw potential for discoveries related to microbial diversity and biological functions awaiting in urban environments.

The study was conducted by the International MetaSUB Consortium (short for Metagenomics and Metadesign of Subways and Urban Biomes), a non-profit research organisation founded in 2015 by Mason and Dr Evan E. Afshin. ETH Zurich has been actively contributing to the consortium since 2016. Researchers from the Biomedical Informatics Lab, Professor Gunnar Raetsch, research associate Andre Kahles and their doctoral students Harun Mustafa and Mikhail Karasikov, also released a searchable, global DNA sequence portal (MetaGraph) that indexed all known genomic sequences. Its capability to map any known or newly discovered genetic elements to their nearest-matching location on Earth was directly applicable to the MetaSUB data and can aid in the discovery of new microbial interactions and putative functions. “Harun and Mikhail worked for three years on fast search algorithms and on new ways to index this type of data. Their advances were essential in making the MetaSUB data fully searchable”, says Kahles.

The new research has implications for detecting outbreaks of both known and unknown infections and for studying the prevalence of antibiotic resistant microbes in different urban environments. It also can contribute to new discoveries about the evolution of microbial life and has many potential practical applications. The researchers have found more than 800,000 new CRISPR arrays and the findings also indicate the presence of new antibiotics and small molecules annotated from biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that have promise for drug development. “One of the next steps is to synthesise and validate some of these molecules and predicted BGCs, and then see what they do medically or therapeutically,” Mason says. “People often think a rainforest is a bounty of biodiversity and new molecules for therapies, but the same is true of a subway railing or bench.”

Reference

Cell, Danko et al.: external page “A global metagenomic map of urban microbiomes and antimicrobial resistance” DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.002